Give your contracts the attention they deserve

Companies creating lovable moments with contract management

.webp)

Contracts here, there and everywhere. Where would you even begin?

One place for all your company's contracts, insights and processes.

Make better decisions with insights at your fingertips

Let us do

the work for you

Ditch the admin work. We’ll extract the essentials from your towering stack of contracts, leaving you free to sit back and relax.

Know your contracts better

Put the spreadsheet, Drives, and physical files away. Find the info you need in seconds and act on crucial contracts immediately.

Catch them while you can

Gone are the days of that renewal, expiry or deadline slipping by. Set tasks in a few clicks and save yourself the headache.

Folks see the value.

Let them speak.

Explore how Contractbook can bring you clarity and peace of mind.

Keep the chaos away

Dedicated contract solutions for all teams, so you

can maintain your overview.

Get deals to the finish line quickly

Generate drafts in seconds from your CRM or other tools

Catch renewals with automatic reminders and tasks on every contract

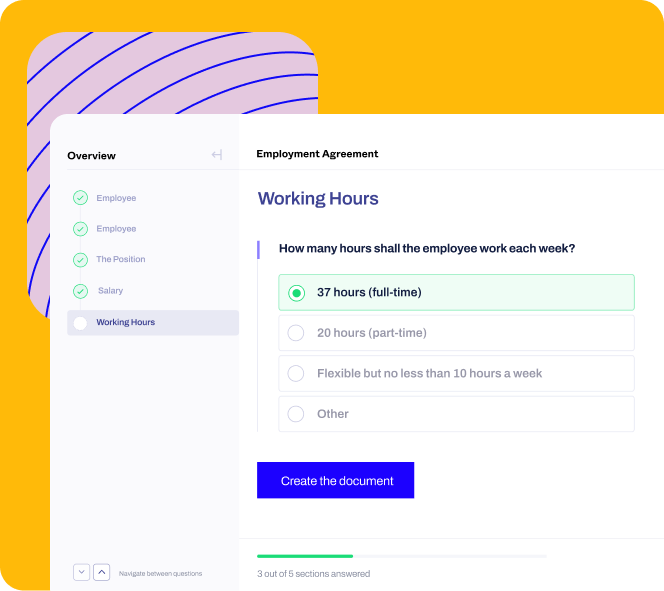

Make the first day a great one

Speed up contract creation with master templates fit for all scenarios

Put admin on auto-pilot with a seamless transit of data to HRIS or payroll tools

Regain your

valuable time

Automate standard contracts withself-serve drafting

Ensure compliance and control with edit-proof templates

Connect your contract data with 3000+ tools.

Schedule a quick product demo

Our team will guide you through key features that are relevant to you and your business

After submitting the form, you'll be able to schedule a time that's most convenient for you

Our team will guide you through key features that are relevant to you and your business

After filling the form, you'll be able to schedule a time that's most convenient for you

.svg)

-1.svg)